For my first few decades of being around vegans and veganism, I would have written the title of this post as a statement: “Veganism: The Place Where Ethics and Health Can Meet.” Now, it seems that these two tenets of the veganism to which I was introduced back in 1970 may be at odds. I’m hearing from more and more people whom I admire that “health shaming” is widespread among vegans and “plant-based” people, while veganism has nothing to do with health, only compassion, as evidenced by The Vegan Society’s current definition of the word:

Veganism is a way of living which seeks to exclude, as far as is possible and practicable, all forms of exploitation of, and cruelty to, animals for food, clothing or any other purpose.

That’s certainly why I’m vegan, but I have to say that I’m a “health vegan,” too, and I’d like to explain why. When I started looking into veganism, it was a very, very esoteric lifestyle, espoused by a mere handful of people. When I opted to go to the UK to study vegans for my college fellowship in 1980, my proposal was accepted by the school because that research could not have been done in the U.S.: there were just too few vegans.

Even vegetarians in the 1970s and early 80s were seen as “cranks” (Crank s was, in fact, the name of a chain of health food stores and vegetarian cafes in London at that time). Veganism — when someone heard of it, which most people didn’t — was seen as extreme, even dangerous. Virtually all physicians were against it, despite some early voices in the wilderness stating its benefits, such as a 1961 passage in the Journal of the American Medical Association which stated: “A pure vegetarian diet can prevent 90% of our thrombo-embolic disease, and 97% of our coronary occlusions.” In other words, long before Ornish or Esselstyn, some experts had figured out that animal foods were behind the heart disease epidemic. “Pure vegetarian” meant “dietary vegan.”

s was, in fact, the name of a chain of health food stores and vegetarian cafes in London at that time). Veganism — when someone heard of it, which most people didn’t — was seen as extreme, even dangerous. Virtually all physicians were against it, despite some early voices in the wilderness stating its benefits, such as a 1961 passage in the Journal of the American Medical Association which stated: “A pure vegetarian diet can prevent 90% of our thrombo-embolic disease, and 97% of our coronary occlusions.” In other words, long before Ornish or Esselstyn, some experts had figured out that animal foods were behind the heart disease epidemic. “Pure vegetarian” meant “dietary vegan.”

Even so, I knew personally vegans who had children removed from their homes by the authorities simply because they had no milk in the refrigerator. We were warned of impending deficiencies in calcium, iron, iodine, various amino acids, and the one deficiency that really had cost the lives of some of the earliest vegans, vitamin B12. Because this was the landscape of the time, every ethical vegan that I knew of was, to some degree, a “health vegan,” too. We had to be. To do anything less than eat as nutritionally as we knew how and maintain the best health we were able would further veganism’s bad rap. We didn’t look at this as way to live forever or look like somebody on the cover of a magazine, but simply to do our best to prove that people could live compassionately and be as healthy as anybody else.

There was another reason why vegans at that time saw the ethical and health aspects of this lifestyle as going hand in glove: we didn’t want to use drugs. They’re certainly not vegan. All have animal testing in their history and money spent on them lines the pockets of the biggest animal testing concern going, Big Pharma. Some also contain slaughterhouse byproducts. When Nathaniel Altman was researching his 1974 book, Eating for Life, the first book about vegetarianism published in the United States since the 1800s, he toured slaughterhouses as part of his research. At one of them, he saw a large bucket filled with especially vile parts and pieces of slaughtered animals and he asked if those would go into sausage. The worker replied: “Those are too good for sausage; they’ll go for medicine.”

In order to avoid the animal-testing-and-exploitation system entirely, early vegans frequented and funded London’s Nature Cure Clinic, featuring modalities such as water-only fasting, juice cleansing, dietary modifications, herbalism, chiropractic, osteopathy (in the UK, osteopathy is a drugless healing art), acupuncture, and homeopathy. When I did the research for my paper (which became my 1985 book, Compassion the Ultimate Ethic), I met some of the old-timers who, for ethical reasons, were as unwilling to partake of medical drugs as any Christian Scientist. Nowadays, I don’t know anyone like that. We’re either more pragmatic or we’re in a state of denial that allows us to feel comfortable confronting someone about honey or silk, while we support the pharmaceutical industry. We do it for good reasons, I know, and I do the same myself when more natural methods fall short. I’m simply saying that veganism’s connection to healthy living and “health food” grew from a sincere desire to eliminate as much animal suffering as possible.

In addition, and probably because of vegans’ reluctance to use their services, virtually no medical doctors were part of the vegan movement in its first forty years. I remember when Dr. Michael Klaper showed up at Vegetarian Summerfest in 1984. I got chills. “We have an MD. Wow!” Obviously, it’s different today. We have lots of medical doctors onboard. Some are committed ethical vegans. In addition to Dr. Klaper, these include Neal Barnard, MD, of Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine, and Michelle McMacken, MD, on staff at Bellevue Hospital in New York City and assistant professor at NYU School of Medicine. (I’m also proud to say that she presents for most Main Street Vegan Academy classes.) Many of the other MDs who espouse plant-based eating (a term we hadn’t heard back in the day) are not interested in animal rights, but a large number do open up to it. These physicians are no different from the great many laypeople who stop eating animal products for their health, quickly learn about animal issues, and join us on the ethical side.

Something else that’s different today from my early experiences as a vegan-leaning vegetarian and ultimately, in 1983, a vegan in earnest, is that being a so-called “junk food vegan” at that time would have been nearly impossible and horribly boring. There was seriously almost no vegan junk food. We had soda. Potato chips and Fritos and French fries (although the fries were usually cooked in animal fat and we avoided them for that reason). Hydrox cookies (Oreos weren’t vegan yet). Twizzlers. Smarties (Liz Dee, a lovely ethical vegan, is a vice-president at this family-owned company). A not widely available chocolate bar called “Goldenberg’s Peanut Chews.” Planter’s Peanut Bars. (None of these sweets were technically, technically vegan, because at that time all white sugar was processed using bone char.) White bread. Margarine and hydrogenated peanut butter (although we thought those was good for you — nobody was talking about the trans fats they then contained).

The “junk” food available was so limited that we focused on fruits, vegetables, legumes and soy foods, whole grains, and nuts and seeds for pleasure as much as anything else. Who would want to live on Coke and Hydrox cookies and white bread with margarine? Even those of us who indulged in these processed and minimally nutritious foods when we felt like it — I certainly did — were still eating mostly whole plant foods. (Of course then we didn’t say that we ate plants; that would have sounded like chowing down on the philodendron.)

Today, of course, we have a plethora of packaged foods imitating — and often surpassing — their animal-derived counterparts. I’m thrilled that they exist because they make it easier for people to go vegan, and now that I can have nut-based vegan cheese or a really great vegan cupcake, I’ll do that on occasion rather than go for potato chips and Twizzlers. I don’t even classify most of the processed vegan foods available today, especially those from companies owned and run by vegans, as “junk.” They might be processed, sure, and they might be rich, and have more salt or sugar or fat than someone like me would choose to eat on a regular basis, but most are, in my opinion anyway, good quality foods.

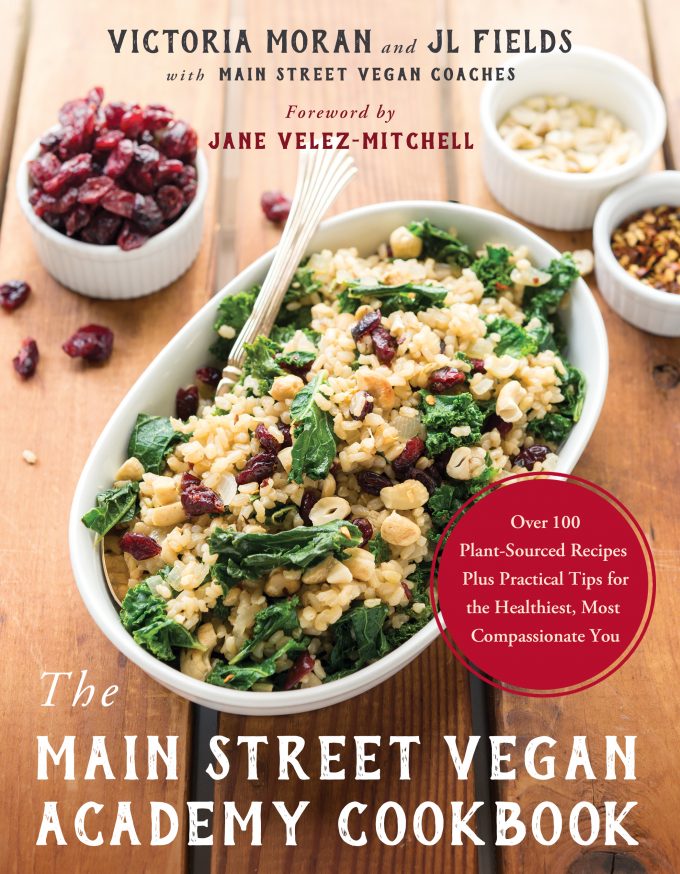

In addition, we’ve figured out how to concoct homemade vegan delicacies that replicate soups, entrees, and desserts that have traditionally contained animal products. This is sheer culinary innovation! I’m so excited that JL Fields, some sixty Main Street Vegan Academy graduate coaches and faculty members, and I will be sharing some of this innovation in The Main Street Vegan Academy Cookbook. Some of the recipes are gustatory ventures into the land of the epicure. Others are more suited to a “crank” like me. While I absolutely claim my right to have brownies and chocolate mousse, I’ll go for the brownies made from walnuts, dates, and cocoa, and the mousse made from avocado, cocao powder, and a little maple syrup, rather then some other vegan version that might contain a lot of sugar or coconut oil, high in saturated fat. Do I mind if a fellow vegan wants to enjoy those? Of course not. It’s none of my business what another vegan eats. I am proud to be part of the growing vegan brother-and-sisterhood that circles the globe, and includes all kinds of people, at all stages of life, eating all kinds of vegan food. For me, choosing primarily foods that I believe support my health and well-being is part of the picture.

Victoria Moran is the director of Main Street Vegan Academy, the author of Main Street Vegan, and coauthor with JL Fields and Main Street Vegan Academy coaches of The Main Street Vegan Academy Cookbook, available now for preorder. She is currently tending to her “health vegan” side at the Ocean Jade Health Retreat in Lauderdale-by-the-Sea, Florida, where she is doing a water-only fast under the supervision of Dr. Frank Sabatino.

Great article! I too am a health conscious vegan, but I deviate very happily from my chia-walnut-kale path at least once a week. Love all the vegans in the whole world.

Peace and merry eating!

Thanks, so much Isabelle! I am crazy about your sentence “Love all the vegans in the whole world.”